It’s fitting that I’m posting my annual writing review three months into the following year and three years since the last one. Since I’m allegedly “goal-oriented,” I created some goals for 2022, which will have to suffice for this 2023 review.

2022 Writing Goals:

- Finish draft of memoir.

- Write curiosity essay and “reader” essay.

- Support and promote writing by others.

- Read at least 2 books a month

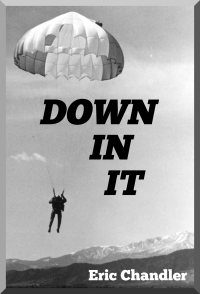

I managed to finish a draft of my memoir. Finally accomplished item #1. I sent it off to the Veterans Writing Award contest that’s administered by Syracuse University in New York. I worked pretty hard on it the previous 3 years and submitted it to them in March of 2023. After I did that, I had what I’d call a writing hangover. I had never written a whole book-length project before. It kind of drained me. I turned my attention to the outdoors and stepped away from the keyboard. At the end of the post, I’ll talk about my big year on the trails. After I scratched my trailrunning/hiking itch, I followed up with the writing contest people and learned that my manuscript “did not advance.” That’s a nice way to put it. At the end of 2023, I sent my manuscript to a professional editor for them to chew on. I got it back before Christmas 2023 with their inputs. I have more work to do on it, which I’m doing now. Daunting to have to keep working on something you thought was done. In some ways this book reminds me of an ultramarathon:You just have to keep moving forward. Stubbornness is an important ingredient in writing and running.

I never got around to #2. I barely remember what I meant by those two essays, but I do indeed remember. I’ll get to them eventually. But the short term ideas that are not WHOLE FRIGGING BOOKS, will have to wait until I’m done with my memoir. I only published two magazine articles last year, largely because I was preoccupied with my book or with my post-submission hangover recovery.

Regarding #3, I enjoy promoting and supporting writing by others. I don’t engage as fully as some people, but I like to share writing by people I know. And even by people I don’t know, especially if the writing resonates with me somehow. I’m hardly a reliable curator, but I do read a lot and pretty intentionally. So, when I find something I enjoyed, I like to tell people about it. Liking and sharing posts on the internet and making book reviews is kind of the coin of the realm for writers. You can genuinely help writers by doing that (hint hint). I try not to be transactional about it. (e.g. I wrote a review for them, they better write one for me) In some ways, when I try to articulate why a book meant something to me, I think it makes me a better thinker, which should, in turn, make me a better writer. It’s a lot like being an instructor pilot. Teaching other people to fly or explaining how to fly to someone else invariably makes the instructor a better pilot.

I didn’t accomplish #4. But I am pretty much at my limit with two books a month and struggle to meet that goal. I do have a day job, after all. But I am just astounded at how well-read other authors and writers are. It’s essentially a time-management question. I love reading. Can’t be a writer without reading. One thing that helps me is that I’ve finally learned how to read two books at one time. I used to only be able to read one book after another. Lately, I find that if I split my reading into Research and Pleasure, I make more progress. I’m filling my head with reading about conservation and public land topics lately, with an eye to a next book. So, I take the Research reading and try to make it something I do after supper for a while, with a pencil in hand, writing notes in the margins and underlining passages. Treating it like homework. Then, I read whatever I want the rest of the time. This usually means a few pages before I throw the book on my bedside table before I pass out. So, I’ve started to take books on the road with me at work. I usually try to travel light, so a book doesn’t meet that goal. But this new habit of bringing a book for fun on the road helps keep me from scrolling on my phone. Worth the extra weight. Maybe this year I’ll hit two books a month.

So, here we go for 2024.

2024 Writing Goals:

- Find an agent/publisher for memoir.

- Support and promote writing by others.

- Read at least 2 books a month

- Rapidly turn short-term ideas into articles/essays.

This is the year to put the memoir into the end zone. I’ll keep doing #2 and #3. I’ve come up with a new thing on Instagram called “Shmo and Tell” where I do a short video review of a book that I like. Not every book that I read, but ones that I want to share something about. I’ve been having a little fun with it. #4 is new. I get plenty of ideas all the time. When I’m not working on my memoir, I can have a little “treat” and hammer out whatever other story ideas are on my mind. I need to be less worried about where they’re going to end up and more worried about getting my words out of my head. My friend Felicia Schneiderhan is a writer and she said this to me once: “Write whatever you want. Nobody reads anything anyway.” Maybe a little glib, but I find it motivational. Write whatever you damn well please.

Another reason I added #4 is because of the loss of Shawn Perich in 2023. He died too young. He had a lot more writing about the outdoors in him that needed to come out. I’m barely a fisherman, but the steelhead are starting to run in north shore streams pretty soon, and it makes me think of Shawn. And then I feel the gap where he used to be. I wrote a tribute to him here, along with a lot of other people. He was a huge part of my growth as an outdoor writer. I miss him.

Books I read:

I reviewed several of these books. You can check out the links below.

Another Nice Thing:

My book of poetry Kekekabic, earned an Honorable Mention in the 2023 Northeastern Minnesota Book Awards for Poetry! That was way cool. You can get a copy at the top right of the front page of this post.

Writing Hangover Cure:

Like I said, I “finished” my book in March 2023 and felt wrung out. So, I ran a trail ultramarathon in May (Superior Spring Trail Race 50k), Grandma’s Marathon (my 15th time), climbed a Fourteener in July in Colorado with Luke and TJ (Mt. Elbert, Colorado high point), and ran my first 50-miler in 13 hours at the end of July (the Voyageur). All of that was to get ready for what I called Shmo’s Big Stupid. I went around the Pemi Loop, 31 miles, 10000′ of climbing in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. It took me 16 hours and 45 minutes. Started in the dark. Finished in the dark. Broke a trekking pole two hours into it. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. And like writing a book, the main things were sticking to the plan and being stubborn. And also like writing a book, by the end, I was hallucinating voices in the creek bottoms and from the rushing Pemigewasset River. If I ever get my book published, because of finishing the Pemi Loop, I’ll know just how good it feels to be done.